Filter by topic and date

Herding the DNS Camel

21 Nov 2018

Bert Hubert, the founder of PowerDNS and author of RFC 5452, shares his views on forces influencing DNS protocol development.

Earlier this year I attended IETF 101 in London. Before flying out I read up on recent Domain Name System (DNS) standardization activity and I found that a ton of stuff was going on. In PowerDNS development work, we had also been noticing that many of the new DNS features interact in unexpected ways. In fact, there appears to be somewhat of a combinatorial explosion going on in terms of complexity in DNS & related protocols.

As an example, DNAME and DNSSEC are separate DNS features, but it turns out DNAME can only work with DNSSEC with very special handling. A recent invention to signal the Key Signing Key (KSK) anchor being used to root-servers turned out to be shut down in production by another RFC which specifies one should stop sending the root-servers queries once they say they have no answer. Oops.

My worry about these colliding features led me to propose a last minute talk (slides, video) to the DNSOP Working Group, which I tentatively called “The DNS Camel, or, how many features can we add to this protocol before it breaks”. This ended up on the agenda as “The DNS Camel” (with no further explanation) which intrigued everyone greatly.

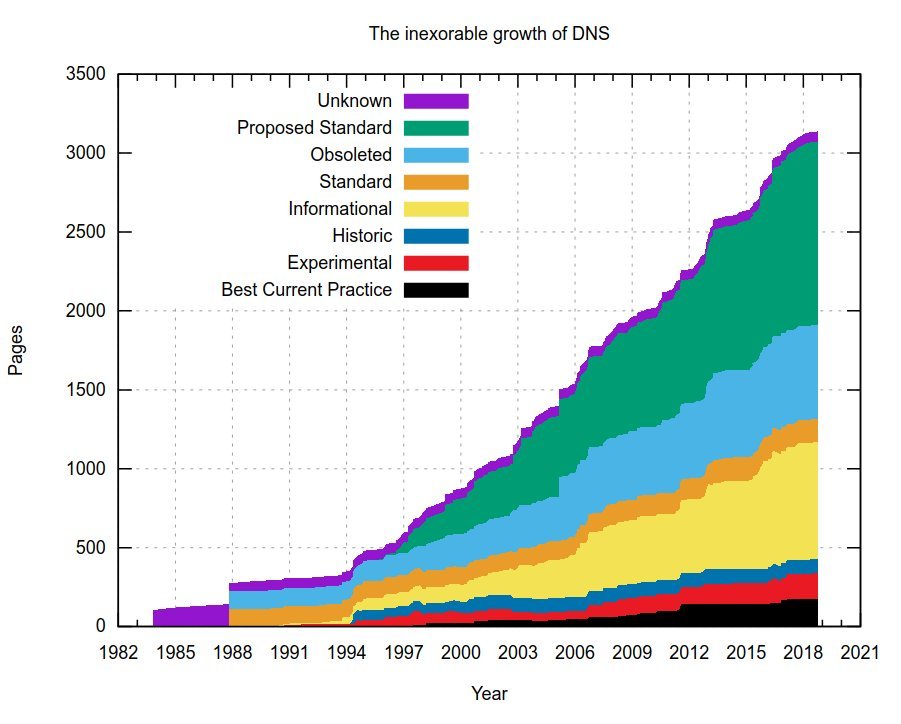

In the presentation, I noted that the growth of DNS has been inexorable over the past three decades and that such growth is not harmless - we can not expect DNS developers and users to read thousands of pages of dense text before they can do their work. And in fact, it is observed that most DNS implementations clearly have not read all these thousands of pages.

If growth continues unabated, we will reach the point that the complexity of DNS is such that no one will be able to grasp it all. This in effect would make it impossible to write any new DNS implementations.

The presentation also explored the reasons behind this growth, in which I focused on DNS-specific mechanisms. In short, we have a very active open source implementation community that provides little pushback on new features. We dutifully implement most new drafts, even when this is very hard work. Force and counterforce are required for any system to be in equilibrium.

The pressure not to implement new protocols in software is traditionally supplied by vendors wary of the cost of implementing them, a counterforce that is not as strong in open source implementations.

Similarly, operational requirements usually provide a "pull" for new features. But that operational community is usually aware how much work it would be to deploy and maintain all those features in production so it can also push back. Oddly enough, the (sizeable) non-root DNS operational community is largely absent from IETF discussions so they neither provide a lot of requirements for the standardization efforts to consider, or pushback on specific initiatives.

So what is the force behind the huge growth in RFCs? It turns out that this is the standardization community itself! Most of the activity behind Internet-Drafts, which become RFCs, isn’t led by any operational requirement but rather stems from feelings by standardizers that things should be “improved”.

Authoring an Internet-Draft and getting it published as an RFC is an achievement, a CV-worthy accomplishment. People work hard on it. In fact, within many employers, getting such documents issued is actually an agreed performance target. “Well done”.

So the growth in DNS standards text is far from an accident–it is baked into our constellation of active standardizers, willing implementors, and lack of operational guidance to hold us back.

I ended my presentation with a call to think hard before adding new stuff to DNS. Audience members also pointed out that demanding reference implementations could put a brake on overzealous standardizers.

But now what?

Although my story was well-received, and the “DNS Camel” would be mentioned a lot during the rest of the IETF 101 meeting week, some people pointed out correctly that I had not contributed any actual ideas on how improve the state of DNS. I spent some time thinking over what could be done, and this led to a presentation (video) at the recent DNS Operations, Analysis, and Research Center (DNS-OARC) meeting in Amsterdam. Here are some ideas:

Stop writing new RFCs!

As long-term DNS developer Robert Edmonds noted, telling people who get paid to do X that they should stop doing X tends not to go down very well. To this, Randy Bush noted that “dns is an industry, cf. icann. but dns standardisation has been an industry in its own right.” Besides requiring multiple interoperable implementations before letting a document proceed towards becoming an RFC, there is little we can do. A show of hands at DNS-OARC made it clear that most of us 1) had written an Internet-Draft, 2) agreed there are too many of them 3) are still working on more of them. PowerDNS (my company) is no exception to this unfortunate situation.

Rewrite / mop up existing RFCs

Besides there being too many pages of standards text, a big problem is that even the most trivial of questions tend to “fall through” several layers of RFCs before the answer is reached. For example, getting clarity on fairly basic DNSSEC NXDOMAIN things requires reading RFCs RFC 7129, RFC 6840, RFC 5155, RFC 4033-RFC 4035, RFC 2181 and, of course, RFCs RFC 1034-RFC 1035.

If we had resources available, we could do the world a great service by rolling up many of these documents into revised editions. For example, RFCs 1034, 1035, RFC 1982 (Serial number arithmetic), RFC 2181 (Clarifications) and RFC 4343 (Case sensitivity) are clear candidates for merging and modernising.

Sadly, our community is not functional this way. We trip over even simple efforts to clarify the meanings of important DNS words. We’d struggle to standardise that drinking water is good. So a formal effort to “redo DNS RFCs” does not seem likely to succeed.

One thing that does seem possible is for a subgroup of DNS people to sit down and create a non-normative retelling of the foundational DNS RFCs in modern language, while incorporating relevant updates from later RFCs.

Obsolete existing RFCs

We looked, but it turns out that of the hundreds of documents, most are either necessary or don’t get read anyhow. We might be able to obsolete two or three, but this does not really address our problem.

Making DNS more accessible

Although our original problem is “there is too much DNS”, the actual issue is that new implementers simply do not know where to begin. Most of us spent more than 15 years getting to know DNS, so we do not have this problem. But to a new entrant, the barrier to entry is almost insurmountable.

This is what I decided to focus my efforts on. With help from the community we now have the following resources available:

- The Camel Viewer: This is a website that shows all RFCs relevant to DNS, split up in "core", "uses DNS", or "rrtype". It also separates out standards (track), BCPs, Informational, historical and other documents. The Camel Viewer has recently been rebranded as the Protocol Camel and a BGP version exists too.

- Hello-DNS: An effort to explain DNS using fresh language which attempts to not oversimplify but still be a readable first entry-point to DNS. Much inspired by the works of Richard Stevens who provided a similar service for TCP/IP and Unix.

- tdns, tauth, tres: teachable DNS API/Library, Authoritative Server and Resolver respectively. Modern DNS libraries and servers are very powerful and optimized, making them unsuitable as ways to "learn DNS by reading code". The goals for tdns, tauth and tres are to remain readable and also serve as vehicles for implementing reference implementations for new drafts. In addition, the hope is that this software displays best practice behaviour, which may get copy-pasted.

In particular, "Hello-DNS" attempts to split out the story of DNS into parts so that new entrants in the field can focus on the pages that are relevant to them. For this purpose, there is dedicated material for authors of stub resolvers, authoritative servers and even full resolvers. In addition, there are separate pages on TSIG, Dynamic Update, DNSSEC and other specific parts of DNS.

Of specific note is the link between "tdns" and DNS Flag Day, scheduled for 1 February 2019. On DNS Flag Day, most DNS resolver implementations will cease to implement workarounds for servers that drop EDNS-adorned queries. `tdns` has never implemented such (or any) workarounds. Based on this, there is now a "DNS Health" viewer which attempts to resolve a top-1000 list of domains using "tres", which implements no workarounds at all and only works with standards-compliant authoritative servers. The output has proven to be educational, but the great news is that as of 2018 the vast majority of domains resolve well without workarounds.

This work is far from done and contributions are more than welcome.

Summarising

The growth of DNS (or of most protocols in fact) is unlikely to stop anytime soon. Even today there is already too much text. We should make multiple interoperable implementations of proposed drafts mandatory, but this will likely on its own not make our protocols more understandable. Although it would be very worthy work to redo three decades of standards into shorter "flattened" documents, we are unlikely to succeed at this effort. It may however (just) be possible to create a non-normative and up-to-date retelling of the foundational DNS RFCs (1034, 1035, 1928, 2181 and 4343, for example).

In addition, it is however possible today to make existing protocols more accessible by providing lists of relevant RFCs and STDs, explaining what they are about, and summarising their contents well. Finally, there is benefit in providing simple reference implementations that will help spread best practices.

If you want to help, all projects and pages above welcome your contribution through GitHub:

Hello-DNS including tdns/tres/tauth

DNS/Protocol Camel RFC viewer

DNS Health viewer

Note: My “DNS is too big” story is far from original! Earlier work includes “DNS Complexity” by Paul Vixie in the ACM Queue and RFC 8324 “DNS Privacy, Authorization, Special Uses, Encoding, Characters, Matching, and Root Structure: Time for Another Look” by John Klensin. Randy Bush presented on this subject in 2000 and even has a slide describing DNS as a camel!

Bibliography

-

[1]RFC 7129

Authenticated Denial of Existence in the DNS

Authenticated denial of existence allows a resolver to validate that a certain domain name does not exist. It is also used to signal that a domain name exists but does not have the specific resource record (RR) type you were asking for. When returning a negative DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC) res…

-

[2]RFC 6840

Clarifications and Implementation Notes for DNS Security (DNSSEC)

This document is a collection of technical clarifications to the DNS Security (DNSSEC) document set. It is meant to serve as a resource to implementors as well as a collection of DNSSEC errata that existed at the time of writing. This document updates the core DNSSEC documents (RFC 4033, RFC 4034…

-

[3]RFC 5155

DNS Security (DNSSEC) Hashed Authenticated Denial of Existence

The Domain Name System Security (DNSSEC) Extensions introduced the NSEC resource record (RR) for authenticated denial of existence. This document introduces an alternative resource record, NSEC3, which similarly provides authenticated denial of existence. However, it also provides measures agains…

-

[4]RFC 4033

DNS Security Introduction and Requirements

The Domain Name System Security Extensions (DNSSEC) add data origin authentication and data integrity to the Domain Name System. This document introduces these extensions and describes their capabilities and limitations. This document also discusses the services that the DNS security extensions d…

-

[5]RFC 4035

Protocol Modifications for the DNS Security Extensions

This document is part of a family of documents that describe the DNS Security Extensions (DNSSEC). The DNS Security Extensions are a collection of new resource records and protocol modifications that add data origin authentication and data integrity to the DNS. This document describes the DNSSEC pr…

-

[6]RFC 2181

Clarifications to the DNS Specification

This document considers some areas that have been identified as problems with the specification of the Domain Name System, and proposes remedies for the defects identified. [STANDARDS-TRACK]

-

[7]RFC 1034

Domain names - concepts and facilities

This RFC is the revised basic definition of The Domain Name System. It obsoletes RFC-882. This memo describes the domain style names and their used for host address look up and electronic mail forwarding. It discusses the clients and servers in the domain name system and the protocol used betwee…

-

[8]RFC 1035

Domain names - implementation and specification

This RFC is the revised specification of the protocol and format used in the implementation of the Domain Name System. It obsoletes RFC-883. This memo documents the details of the domain name client - server communication.

-

[9]RFC 1982

Serial Number Arithmetic

The DNS has long relied upon serial number arithmetic, a concept which has never really been defined, certainly not in an IETF document, though which has been widely understood. This memo supplies the missing definition. It is intended to update RFC1034 and RFC1035. [STANDARDS-TRACK]

-

[10]RFC 4343

Domain Name System (DNS) Case Insensitivity Clarification

Domain Name System (DNS) names are "case insensitive". This document explains exactly what that means and provides a clear specification of the rules. This clarification updates RFCs 1034, 1035, and 2181. [STANDARDS-TRACK]